Margin of Safety #8: AI Might Not Be Coming For Your Job

Jimmy Park, Kathryn Shih, Meryam Bukhari

April 1, 2025

- Blog Post

The Economics of AI Disruption

The news is full of discussion about AI’s impact on the economy. White collar workers are going to see 30% job cuts. Jevons’ paradox means NVidia wins if models get cheaper. But how true are these assumptions? In reality, both the claims of job cuts and chip demand are looking at similar questions: what happens to total consumption of a good — be it labor or GPUs — when cost goes down?

Let’s take a more rigorous look at the claim that AI is going to drive huge job cuts. Before we do that, we’ll go through a refresher on each of economics and AI automation: skip any refresher that you don’t think you need.

Economics refresher

One concept we’ll be returning to is price elasticity – this refers to how much demand for a good changes in response to price changes. Elasticity is generally negative, meaning that as cost goes up, demand goes down. I’m (literally) addicted to my morning latte, but if a latte hits $10 I’ll deal with the headache (or switch to tea, a substitute good). If elasticity is zero, then it means that people have a fixed amount of something they want and they don’t care about price. Price elasticity applies to all markets including the ones for labor.

There are many factors that can influence price elasticity, but a couple big ones for our purposes include the availability of substitute goods (eg, is there something like tea that can be swapped for coffee, under the right conditions?) and whether the good continues to be useful (aka have utility) if someone consumes a higher quantity of it at a lower price. An example of a good that generally doesn’t have that property is insulin: demand is inelastic because people who need it require a set quantity based on their personal biology. Cheaper prices won’t make it more useful, and higher prices won’t make it less critical.

Another thing we’ll be discussing is Jevons paradox. This paradox states that when the efficiency of using a resource goes up, the increased efficiency drives reduced prices and thus increased demand – enough so that total consumption increases, despite the efficiency gains. A key thing to recognize about Jevons paradox is that it requires demand to be relatively elastic. If demand only increases a little as the price drops, then total consumption will still decline. If you’ve been following AI news lately, you’ve probably heard that Jevons paradox means that DeepSeek’s success or NVidia’s new efficiency gains means we’ll need *even* more GPUs.

To understand labor dynamics, we look at market equilibrium, where labor demand(Qd) meets supply(Qs) at a given wage (or more formally, when Qd=Qs). As workers upskill or firms need more output, equilibrium shifts, changing both job numbers and wages. If automation increases work productivity, firms may require fewer employees per task but could expand operations, increasing total labor demand. The interplay between these forces determines AI’s actual impact on employment levels.

AI automation refresher

When we think about AI automation, it’s worth being explicit about the unit of automation. In general, we see things automated at a task level, where a task is a repeatable category of work. For example, scheduling meetings or processing expenses are tasks. Similarly, OpenAI’s Deep Research attempts to automate the information gathering task that occurs within research reports. But the jobs that contain these tasks often have much broader scope and greater diversity.

Someone tasked with gathering data ala Deep Research will often also be tasked with converting that data into a specific point of view or recommendation. Organizations don’t just want to know what others think of a topic; they want to form singular, internally consistent views of their own. Similarly, an executive business partner might handle tasks like scheduling meeting or managing expenses, but they’ll also handle a diverse set of project management and logistics tasks, support change management programs, funnel the most relevant information to the executives they work with, ensure commitments are met, etc.

Onto the interesting stuff: Is AI coming for your job?

The core assumption we keep hearing is that automation will allow fewer people to do the same work, so a bunch of folks will find themselves out of a job. But is this really how it’ll play out? First, because automation affects tasks rather than jobs, we should expect that many jobs see partial versus full automation. This means the cost of the job will go down, but human labor will still be required; it’ll just be more productive and thus valuable labor than before. If cost goes down and demand for this job isn’t fully inelastic, then we’ll see at least *some* increase in total work available.

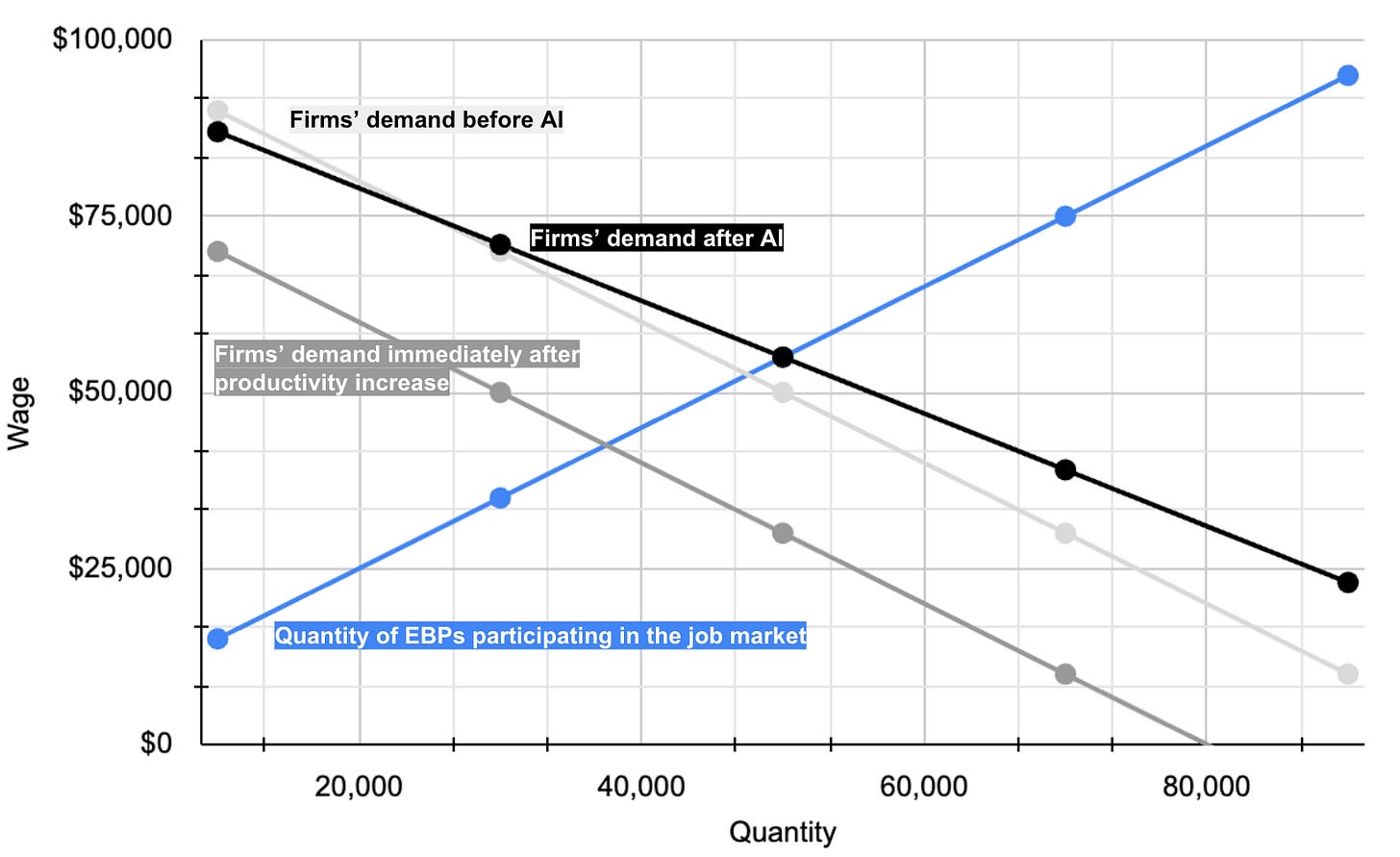

The question is then which fields have more or less elastic demand for automation-ready tasks. While you can try to approximate elasticity by studying jobs data, that’s (1) exceedingly hard to do, (2) won’t shed light on the mechanics of disruption in the job market. Let’s instead walk through how the need for labor affects job quantity and wages, using the market for Executive Business Partners(EBPs) as an example. For this example, we’ve made up some hypothetical supply and demand lines to illustrate the point.

Pre-AI, supply of EBPs (blue line) and demand (ight gray) intersect at $48K and 53K jobs. After AI adoption, firms lower wages before worker behavior adjusts. A new demand function, Qd = 80K – Wage, shifts equilibrium to $38K and 43K jobs. As AI-empowered EBPs boost efficiency, firms gain customers, expand operations, and need more management and thus EBPs. Demand changes to Qd=95K-.8Wage, pushing equilibrium to 55K jobs – higher than pre-AI levels.

This example illustrates how AI adoption can lead to short-term wage adjustments and job reductions but, in some cases, create long-term employment expansion (a la Jevons paradox). The key variable is whether AI-driven productivity gains result in firms growing and requiring more labor or simply reducing headcount to cut costs.

Putting it all together: What actually happens to employment?

There are a few assumptions you could make in which Jevons paradox might not hold for AI consumption, especially in the short to medium term. Note that we focused on what happens to Qd. This is because the narrative of job cuts is told from firms’ POV: eg. “if AI can do X then we don’t need people to do X”. So, if a firm is operating in a space where there is no way to create better products, operate more efficiently, or otherwise compete for customers then they can reap the productivity gains (step 1) without increasing output (and without reaching step 2). Also, in that case, AI-led productivity gains are only speeding up inevitable job cuts. Consider also the EBPs that may be staffed on areas that are not really sensitive to price, “price inelastic”, like corporate information security programs. There’s a minimum human touch required because of regulation and common sense to make sure companies’ data isn’t stolen and programs are run exactly as intended. Those roles are less likely to be affected by job cuts in the first place and also but they also don’t convert as much of the efficiency gains into productivity so aren’t subject to this paradox.

Longer term, the jobs picture becomes even more murky. Most technological revolutions bring disruption to existing jobs, but also the discovery of entirely new job categories. Mobile completely decimated some industries – remember when Garmin specialized in maps for your car? – but it also drove the creation of whole new ones, such as the influencer economy. But when a technology is new, it’s often the case that it’s easiest to frame it in terms of the tasks and industries we already know. This makes it easy to identify the job categories that face disruption, but harder to predict what new categories may emerge.

So you’re saying everything I’ve read is wrong?

Not necessarily. All the authors here are bullish on AI, but we also all believe that it’s better to deeply understand the assumptions underlying your bets and recognize that large scale disruptions take effect in phases. How exactly workers, executives, and customers respond will determine what happens in the economy. If labor becomes more productive but not in a way that helps firms compete, then jobs will likely reduce. If firms see more productivity and are run efficiently, then they’ll repurpose employees to continue growing revenues. If we’re going to bet on Jevons paradox or AI driven workforce disruption, we should think critically about the forces that will cause (or not cause) those bets to come true.

What do you think – which verticals do you think will benefit most from AI and what new categories of work will emerge? Do you know of a company that’s repeated the benefits – or been hurt – by AI already?

Stay tuned for more insights on securing agentic systems. If you’re a startup building in this space, we would love to meet you. You can reach us directly at: kshih@forgepointcap.com and jpark@forgepointcap.com.

This blog is also published on Margin of Safety, Jimmy and Kathryn’s substack, as they research the practical sides of security + AI so you don’t have to.